Artists call it different names, sinking-in, dead spots, ghosting, blotchiness, and it can be one of the biggest frustrations for oil painters. When your beautiful painting dries, certain spots appear dull and devoid of color. So how can you prevent dull patches from happening in your oil painting?

You can prevent oil paint from sinking-in by using a thick over thin or fat over lean painting technique, and by painting on properly prepared substrates to prevent absorption. If sinking in still occurs, the problem can be corrected by oiling-out the painting surface.

Let's take a look at how sinking-in occurs and what to do about it.

What is Sinking In?

Sinking-in, or ghosting is when the oil in the upper layers of an oil painting gets absorbed into the layer beneath during the drying process. Once the painting is dry, this leaves spots in the upper layer looking very dull, matte, and even devoid of color. This is usually more evident in darker colors.

In most cases, the entire painting surface is not affected, though this can be the case depending on how it happened. Most of the time you will have normal and even glossy spots combined with completely dead spots, resulting in a very uneven appearance.

If you are new to oil painting, this phenomenon may catch you off guard. The good news is this is quite common, even among seasoned professionals, and it's an easy fix.

The Causes of Sinking-In

As stated above, what happens during sinking-in is the oil in the top layer is absorbed into the layers underneath, but how does this happen?

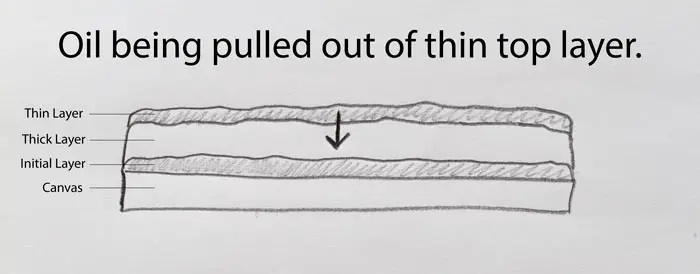

The most common cause of sinking-in is the improper application of oil paint, painting thin layers over thick layers, or painting lean paint over fat paint. If you do either of these, you are almost certain to have ghosting in your work. In either of these cases, the higher oil content in the underneath layers absorbs what little oil is in the top layer.

Another cause can be painting on a highly absorbent surface that has not been properly sized and or primed. For example, if you paint on a bare wood surface, the unprotected wood will absorb the oil like a sponge, leaving little in the pigment. This can be prevented by properly sizing and priming the surface, or glue primed canvas onto the surface.

Let's look at each cause in more detail and how to prevent it.

Keeping It Thick On Top

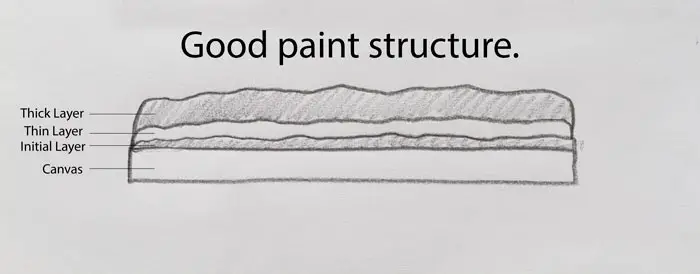

One of the easiest ways to prevent sinking-in is to make sure that your initial paint layers are thin and subsequent layers are thicker. This not only prevents ghosting, but it also results in a more stable painting.

Let's say you like to thin your paint with solvents (mineral spirits or turpentine) to achieve lower viscosity (thinner paint with more flow). This is fine but just make sure that you only do this with the initial layers, using less and less solvent with each subsequent layer.

Once you get to the point of tube consistency (using paint as it comes straight out of the tube), you should cease to use solvent in any subsequent layers.

Bear in mind that you don't need to obsess over how much mineral spirits you are adding or your ratios. No artist uses measuring spoons for this process. Just casually lessen the solvent with each additional layer and keep it out of your top layers.

Keeping It Fat on Top

The second thing you will want to do is make sure that you are painting fat over lean. Fat over lean is sightly different than thick over thin as the term refers not to how thick the paint is, but how much oil it contains. Fat paint has more oil, while lean paint has less oil.

If you are new to oil painting you may think that all oil paint contains the same amount of oil, but this is not the case. Certain pigments have a higher oil content than others and this can also vary depending on the brand of paint. Basically, the shinier the paint, the higher the oil content. Many times you can notice this by looking at the paint itself when you squeeze it out of the tube.

If you stick to the thick over thin principle, you will usually, by default, achieve the fat over lean principle. However, since all pigments do not have the same oil content, there are times when even painting thick over thin may result in some sinking-in.

Some artists will get around this by using an oil-based medium such as linseed oil, Liquin or Galkyd in all of their layers. But this is not necessary as sinking-in can be easily corrected. Also, this may not solve the problem as it's difficult to assess whether you used more or less medium in your previous layers.

While this is not something you want to obsess about while painting, try to avoid using a very oily color, such as Ivory Black, on your initial layers, unless you thin it with a solvent to lessen the oil content. And whatever you do, don't ever thin your initial layer of paint with oil or an oil-based medium such as Liquin or Galkyd. This would necessitate adding tremendous amounts of oil in your subsequent layers.

How to Paint Thin Over Thick

There are times when an artist would need to paint a thin layers of oil paint over a thicker layer. Techniques like glazing require thin paint to be used as a means to shift a color or value. This technique has been utilized for centuries and if done correctly, it will not result in sinking-in.

To properly glaze over thick paint, use oil or an oil-based medium to thin the paint before application. This will ensure that this subsequent layer is fatter than the layer it's being applied to and will prevent sinking-in. You may need to experiment with how much to thin your paint. I recommend testing this on a piece of scrap canvas to make sure the result isn't too shiny or dull.

Make sure you don't thin your painting with a solvent to glaze, unless you are glazing over very thin subsequent layers, and even then you may get sinking-in. Basically the rule is that you can paint thin over thick, but rarely lean over fat. I say rarely because there are caveats even to this rule that we will discuss below.

Substrate Priming and How It Affects Your Painting

One more cause of sinking in that we will look at is painting on very absorbent surfaces. Surfaces like bare wood and untreated paper are highly absorbent. Traditional gesso is also highly absorbent and using it will result in a very matte appearance. Painting on high-absorbent surfaces increases your chances of sinking in.

Acrylic gesso, while less absorbent than traditional gesso, is still fairly absorbent. Oil-primed surfaces are mostly non-absorbent and will result in a glossier finish. With oil-primed surfaces, the more layers of primer there are, the less absorbent the surface will be. So three layers of oil primer will be less absorbent than a single-primed canvas or wood surface.

Oiling Out-The Cure All For Sinking In

So you've done everything right (or perhaps not) and you still have dull spots on your painting. Never fear, that's where oiling-out can come to the rescue.

As stated above, those dull spots don't have enough oil in them. So all you have to do is put more oil in them and they will come back to life again. So let's talk about how to do this.

The first thing you need to do is make sure your oil painting is dry to the touch. It does not have to be completely cured, nor does it require the minimum 3 to 6 months of drying time that some varnishes require. Oiling-out does not seal the surface as some varnishes do, you are merely adding more of what is already there. You also don't need the entire painting to be dry, just the dull part.

Next, you will want to get a hold of some pure, odorless mineral spirits. Do not use the mineral spirits from the hardware store as this stuff usually has additives that you will not want in your painting. Make sure it's an artist-grade mineral spirit like Gamsol or Turpenoid.

The third thing you will need is some type of artist-grade oil or a drying oil-based medium. You can use linseed oil, but remember that linseed oil can yellow over time so you may want to avoid using it over cool, light areas such as white, light blue, or pink. For these areas, you may want to use safflower oil. Keep in mind that if you use a natural oil it will probably take several days or more to dry.

Rather than using natural oil, most artists will use a quick-drying oil medium such as Galkyd by Gamblin or Liquin by Windsor & Newton. These do not yellow and they dry much faster than regular oils. Please note that I have never used Liquin and I'm not sure you can thin it with solvents. I suggest Glakyd by Gamblin as I know this can be diluted with mineral spirits. See the Resources Page for more info.

Next you will need is a clean, soft bristle brush to apply the mixture. A 1 or 2 inch brush from the hardware store usually suffices, as long as the bristles are not real stiff. You don't want to damage and open any thicker paint strokes that may still have wet paint underneath.

The last thing you will need is some clean, lint-free cloth like cheesecloth.

Here is a list with the materials reiterated:

- Artist quality mineral spirits

- Artist quality oil or quick-drying oil medium

- Soft bristle brush

- Lint-free cloth such as cheesecloth

- Jar big enough to fit the paint brush

The Oiling-Out Process

In a jar, blend one part mineral spirits and one part oil medium (or oil) to a 50/50 ratio. You can adjust this ratio if you want less gloss or more gloss. I've known some artists to use just oil medium with no solvent. I don't usually recommend this because if you want to paint over it, you will need to add that much more oil to the subsequent layers.

Apply a very small amount of this mixture to your bristle brush, then lightly apply the mixture with a quick, circular motion over the areas that need oiling, or over the entire painting. Leave the painting stand for about a minute, then wipe off any excess with a piece of cheese cloth.

Be sure not to apply too much, just enough to re-saturate the area. If you are unsure, apply a small amount, wait for it to dry, then repeat if necessary until the area no longer looks dull or blotchy.

Once this area has dried, you can paint over it. Just make sure that any subsequent layers have oil or oil medium added to them to prevent the exact problem you just corrected. If you do encounter more sinking in on the same painting, don't stress, just repeat the oiling out process again.

Sinking-In While Painting Wet on Wet

I've been talking a lot about painting in layers, but what if you don't paint in a grisaille-type manner with complete layers? Basically all this still applies whenever you place any paint over previously applied paint, even if it's in just one spot on your canvas.

It can also apply, though not as much, when painting wet on wet. You may think that since you are laying down wet paint over wet paint, it will all just blend together, but this is only true if you blend the new layer with the initial layers. If you are gently laying down a subsequent layer, while it will stick to the previous layer, it will remain its own layer and could result in sinking-in.

There are times when you can break the rules. One of the most common is dry brushing a small amount of thin, tube-consistency paint onto thicker paint with a very light hand, leaving little openings to the previous paint layer. An example of this may be thin winter tree branches. In this case, you are applying so little paint that any sinking-in will not be noticeable, and since it's a thin stroke of already broken paint, cracking should not be an issue.

Using Varnish to Solve Sinking-In

Since sinking-in results in a dull, flat appearance, you may think that varnishing alone will solve the problem. This is not true. Varnishing will mask the problem by adding a glossy surface over the area that is sinking-in, but it doesn't solve the fact that the sunken-in area still lacks sufficient oil content.

Depending on the type of varnish and how much you apply, you may still have an uneven surface appearance. And even more, concerning is that this area is still brittle. Varnish will not re-saturate the paint, it just sits on top. That brittle area will probably end up cracking someday. Get the surface appearance as even as possible through oiling out before you varnish.

Oiling-Out As a Varnish

That brings up another point. You can use the oiling-out method as a type of varnish for your paintings. There are two great reasons for doing this. The first is that you don't have to wait several months for your painting to dry as you do with many traditional varnishes. You can achieve a glossy surface right away. This is great if you have to display the painting sooner than it can be varnished.

Another good reason is that oiling-out provides a permanent, protective layer of oil over the painting. You can still rework the painting, or varnish it. I like this method better than using retouch varnish since if I have to rework the painting, I'm not adding a layer of varnish between the layers of paint.

To use the oiling-out method for a varnish replacement or a pre-varnish treatment, just follow the instructions as listed above. If you are confident that the painting will require no further working, you can skip wiping off the excess oil-out mixture with cheesecloth (unless it's pooling up somewhere, which would result in an uneven appearance). You can also use a higher oil/solvent ratio for a glossier finish.

Even with the higher oil/solvent ratio you can still retouch the painting, just make sure you have a lot of oil in the paint when retouching.

My Oil Painting Process

I thought I would briefly share with you my typical painting process. While it used to happen a lot, I now rarely have occurrences of sinking-in.

I paint on Classeans Oil-Primed Linen and for the most part, and I use Utretch and Gamblin oil paint (see the Resources Page for more info and where to get these materials). Sometimes I will tone the canvas with Gamblin's Fast Matte oil paint, other times I'll just paint right on untoned canvas.

My first layer of paint is almost always thinned with Gamsol Odorless Mineral Spirits. In most cases, I don't make it too soupy. Once the canvas is covered, I'll either reduce the amount of Gamsol that I add to the paint or start adding thin layers without any solvent. Once I add layers without solvent, I cease adding solvent to any subsequent layers.

I will continue to add thin layers of paint, straight from the tube with no solvents or medium. I add thin layers until I'm confident that my colors, values, and shapes are correct. At this point, I may add some thick paint for texture or surface interest.

With this method, I rarely encounter any sinking-in. The exception is when I have to apply dark paint over dried paint. Knowing this I will usually add a little bit of some type of oil-based medium such as Galkyd. If sinking-in does still occur, then it's time to oil-out.

I hope that helps. Please leave any questions or comments below and keep painting!

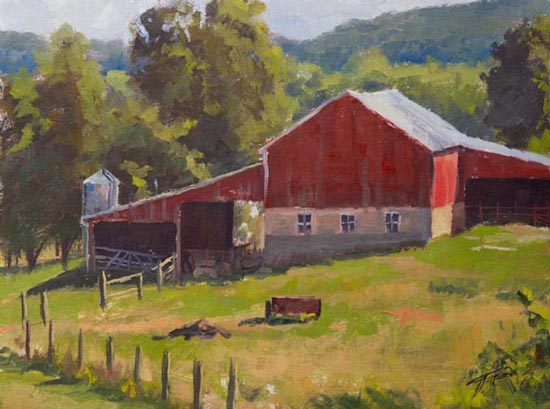

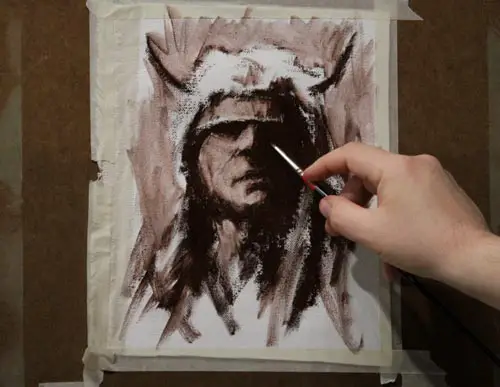

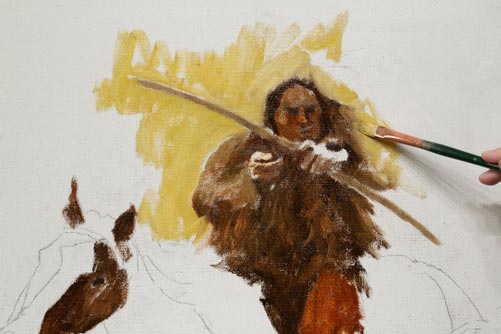

Jason Tako is a nationally known fine artist who specializes in western, wildlife, plein air, and Historical Native American subject matter. He spent his learning years sketching the wetlands and wooded areas of rural Minnesota. He has been featured in Plein Air Magazine and Western Art Collector Magazine and he was the Featured Artist for the 2020 Southeastern Wildlife Expo. See his work at www.JasonTako.com and his demonstrations on his YouTube Channel.

It professional art circles it's called Alla Prima, others call it wet on wet. But no matter what you call it, wet on wet oil painting can give you results that cannot be achieved with other techniques. So what is wet on wet oil painting and how it is done?

A wet on wet oil painting is usually completed in one session. For the best results, the artist should start with a thick over thin technique. Subsequent layers of paint can be applied over thick wet layers by utilizing a gentle paint application with a soft brush or even a bristle brush.

Let's dive into what wet on wet painting is and how to do it without making a big mess.

What is Alla Prima or Wet on Wet Painting?

Wet on wet painting was utilized by Early Netherlandish painters in the mid-15th and 16th centuries, along with Diego Velázquez and Frans Hals. But it really seemed to take off after the invention of the paint tube, which allowed the Impressionists to head outdoors and capture light on location. John Singer Sargent, one of the realist masters of this technique, deserves intense study for wishing to learn alla prima.

The term alla prima is Italian for at first attempt. With most oil painting methods you apply a layer of paint, then wait for it to dry (which can take a while) then apply another layer and repeat until it's done. Wet on dry can drag the completion time of a painting out to days, weeks, or even years depending on the size, subject, and style of the painting, (check out my article on 9 Ways to Make Your Oil Painting Dry Faster.)

With alla prima painting, the paint is applied wet on wet. And while not necessary, the painting is usually completed in one sitting. For larger studio works that take days or even weeks to complete artists can still utilize a wet on wet technique despite the longer completion time. We still discuss this below in more detail.

The Benefits of Wet on Wet Painting

The most obvious benefit of wet on wet painting is that you don't have to wait for days on end for the paint to dry before you add another layer. This not only means you can complete a painting in one sitting, but it also means you can complete more paintings period. While oil painters working wet on dry may only complete a handful of paintings in a year, an artist who paints alla prima can finish hundreds of paintings in a year.

This quick completion time is also great for plein air (on location) painting. Outdoor light can be very fleeting. Even with stable sunlight, you have a maximum of about 3 hours before the light has changed to such a degree that you either have to stop painting or paint from memory. This makes alla prima a very essential option for outdoor painting.

Another benefit of wet on wet painting is that it takes advantage of the beautiful blending opportunities that oil painting has to offer. You can blends different colors together to an almost glassy consistency. You can also easily scrape off mistakes and start again.

The Challenges of Wet on Wet Oil Painting

There are several challenges with wet on wet painting. The first is control. Piling on wet layers of paint can eventually make it difficult to control what is happening on your canvas, especially if those layers are really thick. If you play around too much with those thick layers you will end up with a big mess on your canvas.

The second challenge is over-blending of colors. Since the paint on the canvas is still wet, any paint you put over that can blend into it. This can be advantageous as you can mix colors right on your canvas, but if you are not expecting this, it can be a real problem. We will discuss more about mixing colors on the canvas further below.

The third challenge has to due with judgement and analysis of your work. While completing a painting in one session can give you a feeling of accomplishment, it can also deprive you of the time needed to really analyze your painting for any mistakes or adjustments that need to be made.

When I first got into alla prima painting, I let myself get too hung up on completing the painting in one session. I placed completion time over quality, priding myself that it was all done within several hours. I've since changed my approach. I would rather spend weeks, months or even years on making a painting the best it can be. Who cares if it was done in several hours if it looks bad.

If you are going to work wet on wet, be sure to take as long as needed to make a good painting. What I mean by that is make the fundamentals of good painting your priority. These fundamentals are: composition, drawing, values, color and edges. None of these should ever take a back seat just so you can work within a certain technique or method.

Remember, techniques and methods are the servants of good fundamentals and good results, not the other way around.

Starting Thin and Getting Thick

One of the keys to alla prima painting, and really for any oil painting, is to make sure you keep your first layers thin. While some very experienced artists will start with thicker layers and keep piling it on, it can be maddening to try to make adjustments to thick layers of paint, and unless you know what you are doing, it can turn into a big mess.

A good strategy is to slightly thin your first layer of paint with mineral spirits, or lightly scrub a thin layer onto the canvas with a bristle brush. Get your values and color masses established before your proceed to thicker paint.

One caveat is don't make your initial layer too thin or soupy. Adding paint onto a surface that is saturated with mineral spirits will result in poor adhesion to the canvas and usually leads to a big mess. If the surface is too wet, you may want to let it dry some.

Using a Gentle Hand

When laying down the initial layer of paint onto the canvas, especially heavily textured canvas, you may need to scrub in the colors somewhat aggressively to get the paint to cover the canvas completely. But once the initial layers are on, you will want to use a very light touch when applying the subsequent layers of paint, especially if you don't want the subsequent layers to blend with the initial layers.

For very gentle applications of paint, I like to use what I call the Underhand-Downward Facing Grip. This grip allows you to use the side of your brush to apply the paint (see below). It's nice because you can pile the paint on the brush and gently drag the brush across the canvas. If done right, you will hardly disturb the paint underneath. See my article on different ways to hold a pencil for more ideas. These ideas can apply to painting as well.

Blending and Marbling

As stated above, wet on wet painting allows you to do some nice blending techniques that are not possible when painting wet on dry. Of course, we have all seen Bob Ross and his famous fan brush blending techniques. But that is not the only way to blend. You can use other types of brushes, palette knives, paper towels, and even your fingers to blend wet paint.

Another cool technique is to paint one color gently and smoothly into another color causing them to merge in a way that doesn't actually blend them into a new color, but rather marbles the paint together for an awesome multi-color effect.

Types of Brushes

Any brushes you use for oil painting can be used for wet on wet painting. Many oil painters tend to favor hog bristle brushes. However, alla prima painting works nicely with softer, badger hair or imitation badger hair brushes. These soft brushes work well with wet paint and are wonderful for blending and that gentle paint application discussed above.

See the Resources Page for my recommendation on oil painting brushes.

Palette Knife Painting

Wet on wet painting is great for palette knife painting. When you paint with a palette knife, the paint you apply must have some body to it, in other words, it cannot be thinned since it won't stick to the knife to be applied to the canvas. Applying nice, buttery paint to canvas can seem a bit like frosting a cake, and it's a lot of fun.

The palette knife can also give you textures and effects that you cannot get with a brush. I've done entire paintings with a palette knife and for some artists it's their entire arsenal. Give it a try when painting alla prima, especially for vegetation.

Mixing on the Canvas

While most mixing is done on a palette when working wet on wet you can mix your oil paint right on the canvas instead. However, if are you still new to oil painting I would recommend mixing on the palette for a while until you are confident with your color mixing, or experiment with some scratch-canvas so you don't ruin a painting you want to turn out well.

I usually mix on the palette, but I will mix on the canvas to make slight adjustments to my colors.

Compensate For What's Already on the Canvas

When painting wet on wet, if you are going to do any type of mixing on the canvas, or if you are going to apply new paint onto wet paint with any amount of pressure, be sure you are compensating for what's already bee laid down.

For example, let's say you want to make your sky, which is still wet, a little darker blue. Since the applied sky color probably has a lot of white paint in it, that wet white paint will lighten any color that is added to it. So you will want to mix a slightly darker blue than what you think you will need. This can be a little tricky and many times requires some adjusting before you get the color correct.

Use High Quality Paint

You will have much more success with wet on wet painting, and painting in general if you use quality paint. Trying to paint with stiff paint or paint that has the consistency of whipped cream will make alla prima painting more difficult and even a miserable experience.

If you are not sure where to find good, quality oil paint, check out my resources page to see what brands I use.

Using Slow-Drying Oils

Artists working alla prima usually like to keep their paint wet for as long as possible. You can make this happen by using paints that are made with safflower or walnut oil. These oils dry slower than linseed oil. M. Graham oil paints are made with walnut oil and tend to stay wet longer than other brands.

Another technique is to add poppy oil to your paint. Poppy oil has the slowest drying time of all other oils. So if you want to keep your oils wet for as long as possible, add some poppy oil to them.

Working Wet on Wet and Not Alla Prima

I've been using the terms wet on wet and alla prima interchangeably. While they usually do mean the same thing, there is a slight distinction. Almost always an alla prima oil painting is done wet on wet, but not all wet on wet oil painting needs to be done alla prima.

If you want to paint wet on wet on an oil painting that cannot be completed in one session, there are some techniques that will allow you to still paint wet on wet.

The first is scraping and reapplying. Many suspect this is how John Singer Sargent was able to complete such large canvases in what appears to be a wet on wet approach. Let's say your painting session is over and you have your sky blocked in but the mountains have to wait. You just scrape off the part of the sky colors that adjoin the mountains. Then on your next session, you repaint that section of the sky and proceed to the mountains.

This approach allows you to have the benefit of being able to manipulate the sky and mountain edges with wet paint. Since the sky is generally one color, you don't have to worry as much about those edges, you just have to remix the sky color exactly. Scraping off some of the sky paint during the previous session keeps one area from have thicker textures than the other area.

The one drawback to this approach is that it basically forces you into a finish as you go approach. To work with wet paint at all times on a large, complex canvas, you have to work in smaller sections and complete those sections before the paint dries.

Of course, you are not restricted to a wet on wet approach. If you need to make adjustments on dry paint then do it. Remember that technique should always be the servant of the results, not the reverse.

There are artists who will complete very large canvases in one session. Joaquin Sorolla became a master at this. But I've known artists today who use this same approach. Tim Bell is a modern master of this technique, completing very large plein air canvases withing several hours or less. Bear in mind that this requires a loose approach that focuses more on light and form rather than tight drawing and detail.

Another option, though a bit riskier is to store your unfinished painting in a very cool place, or even in a freezer, provided you have a freezer large enough. Freezing greatly slows the oxidation process that dries oil paint. I store my unused paints in the freezer and some pigments will stay wet for weeks (see my article).

If you decide to try this approach, be sure that the support you are painting on can handle storage in freezing temperatures. Do this by taking perhaps an old painting that is destined for the garbage can and placing it in the freezer. Take it back out after several days, or however long you intend to use this method and see how it holds up.

I would not recommend storing your painting outside in the winter time unless it's in an unheated shed where it will have some protection from the elements. Again, test this approach with an old painting you don't care about.

Creating a Wet on Wet Style

As stated above, wet on wet painting can give you effects and options not possible with wet on dry painting. Many artists who use the wet on wet approach tend to paint in a looser, more impressionistic style. Those who like very tight detail may find wet on wet painting to be a hindrance. Also, painting lots of detail takes time, and time dries paintings, no matter what.

If you are going to paint wet on wet, allow yourself to be open to the looser style that wet on wet painting offers. If you are a tight painter, wet on wet can still offer subtle blending techniques not possible with wet on dry painting. I personally use both approaches. Whichever approach gives you your intended results is the approach you should use.

The most important thing to do is experiment with an open mind that is not obsessed with results, but rather with discovering. Give yourself the freedom to destroy some canvas without having the justify the results. It's not wasting money. Learning is never a waste of money. Every good artist throughout history has done this. And you may find a whole new world of possibilities.

Keep painting!

Jason Tako is a nationally known fine artist who specializes in western, wildlife, plein air, and Historical Native American subject matter. He spent his learning years sketching the wetlands and wooded areas of rural Minnesota. He has been featured in Plein Air Magazine and Western Art Collector Magazine and he was the Featured Artist for the 2020 Southeastern Wildlife Expo. See his work at www.JasonTako.com and his demonstrations on his YouTube Channel.

Waiting for oil paint to dry can try an artist's patience, especially those who are used to faster-drying paint such as watercolor or acrylic. In this article, we will look at 9 different techniques to make your oil paints dry faster.

Paint In A Dry Well-Ventilated Area

As stated above, oil paint dries through a process of oxidation. It actually doesn't dry as does acrylic paint when the water evaporates from the pigment. Rather, oil paint undergoes a chemical reaction that causes the oil to harden.

Painting in a dry, well-ventilated area can significantly speed up the drying process. Exposure to natural light is also said to help. Having a fan run in your studio or on your painting, opening the window (provided it's not humid out), running a ventilation fan (always a good idea when using solvents), and running a dehumidifier can help speed up drying. The constant exchange of air aids the chemical change.

If you run a fan that hasn't been used in a while, be sure the clean any dust off of the fan blades, especially ceiling fans. You don't want all that dust circulating in the air and getting into your painting.

Expose Your Painting to Heat-But Be Careful

You have to be careful with this one, but it works and works well. Exposing your painting to heat can significantly speed up the drying process. The higher the heat, the quicker it dries. The opposite is also true, cooler air will slow down the drying process (see my article on storing unused oil paint in the freezer).

There are different ways to heat up your painting. One safe way is to stick it in a window on a warm, sunny day. Both the light of the sun and the warmth will speed up the process. Another is to just set the thermostat to a higher temperature in your studio overnight, or during the day if you like it hot.

When I used to do summer plein air events I would place a completed painting that was done on linen glued onto plywood in the back window of my car. However, I learned the hard way that you must be very careful with this process. Sometimes the inside of my car got so hot that the linen began to separate from the plywood, and the plywood warped. Keep in mind that many painting panels are made with heat-activated glue.

Some advocate using a heat gun on your oil painting. I have never tried this as I usually work wet on wet, but they claim it works. If you use a heat gun, be sure to keep the setting under 130 degrees Fahrenheit as higher levels could result in yellowing or even cracking the paint. Move the gun slowly over the painting keeping it several inches away. Be sure the gun never touches the painting during this process.

I've experimented with other heating methods that I will not mention for fear of inspiring you to accidentally set your house on fire. Just be certain that if you use any kind of heating technique, don't go overboard and keep it safe. Better to wait a few days for paint to dry than to ruin your painting or burn your studio down.

Apply Your Oil Paint In Thin Layers

Now we move away from environmental factors and onto technical and chemical methods to speed things up. The first being paint application.

Thicker paint takes longer to dry. Oil paint drys through a process of oxidation which changes the paint's chemistry when it's exposed to air. The thicker the paint application, the longer this process takes since the entire mass of paint is not evenly exposed.

There are numerous ways to thin oil paint. Solvents are probably the most widely used method, but you can also use different types of oils, dryers (discussed below) and thin paint application. Bear in mind that if you thin your paint with oil, you will extend the drying time rather than shorten it. You can also thin the paint by just scrubbing it aggressively onto the canvas with a bristle brush without using any thinners (AKA tube consistency).

When painting with thin layers, always make sure the initial layer is the thinnest and has the least amount of oil content of any subsequent layers. This is the thick over thin/fat over lean principle which must be followed if you want to avoid having your painting crack, ghost (produce dull spots, learn more in my other post), or worse.

When painting in layers, I'll start by applying a very thin layer of paint with maybe just a touch of Gamsol Odorless Mineral Spirits (see Resource Page for more info on Gamsol). Slightly thicker layers can be added with tube-consistent paint, leaving the thickest for last.

The great thing about this approach is that the initial layer of thin paint will speed up the drying of the subsequent layers. In many cases, it's the initial layer that takes the longest time to dry.

Knowing this you can tone your canvas with maybe a warm earth tone like Transparent Red Oxide, let it dry, then start painting. If you apply thin layers of paint, many times they will be dry within a day or two depending on other variables which we will discuss below. Just be sure to follow the thick over thin/fat over lean principle.

If you have sensitivity or health issues with solvents, check out my post Oil Painting Without Solvents-What Artists Need to Know.

Use Dryers Such as Galkyd or Liquin

Chemical drying agents such as Galkyd, made by Gamblin, or Liquin, made by Windsor & Newton is a great way to speed up the drying of subsequent layers of paint. Notice I said subsequent because these products and others like them have a petroleum distillates base which acts like oil and therefore must follow the fat over lean principle described above.

Dryers are used by adding a small amount into your paint mixtures prior to applying them onto the canvas. Thin layers of paint can start becoming tacky within an hour, while thick strokes of paint may still take one to several days to dry.

Gamblin makes several different versions of Galkyd with different rates of drying. These dryers also give the paint a glossy appearance. Just be sure to use them as instructed since they generally do have some toxicity.

I've found that Walnut Alkyd, made by M. Graham is probably the fastest of all when it comes to drying time. The nice thing about walnut alkyd is that it's non-toxic, boiled walnut oil. Whenever I want something to be dry the next day, this will be my best bet.

NOTE OF CAUTION: be sure to clean your brushes thoroughly after using any chemical drying agents. Failing to do so will leave you with hardened, unusable brushes. If this happens try Turpenoid Natural for cleaning and restoring your brushes. See more information on this and the mediums mentioned above on the Resources Page.

Use Oil Paints that Contain Linseed Oil Only

Linseed oil dries faster than safflower oil and walnut oil, and poppy oil dries the slowest of all. Most oil paint is made with linseed oil but some manufacturers may use safflower oil in their white paint or in light-valued cool colors since linseed oil has a tendency to yellow after it dries. This will cause these colors to dry at a slower rate.

Some manufacturers may use strictly walnut oil or even safflower oil in some or all of their pigments. M. Graham for instance uses walnut oil almost exclusively in all their pigments. It's a wonderful, high-quality paint, but it's not going to dry as fast.

So if you want to speed up the drying process, avoid paints that use safflower, walnut, or poppy oil and stick with paints made with linseed oil.

Use Alkyd Paint With Your Oil Paint

Alkyd paints are just oil paints made with a quick-drying oil, similar to the walnut alkyd described above. While not as fast-drying as acrylics, alkyds usually dry within a day.

The great thing about alkyds is that you can mix and match them with oil paint or do an entire painting strictly with alkyds. A painting done entirely in alkyds will usually dry overnight, even with thicker paint applications.

If you want to mix and match, a great strategy can be to use alkyds for slower drying colors like whites and cadmiums and stick with regular oils for the rest of your colors. I use this approach for painting trips when I need paintings to dry relatively fast for transportation purposes, but it can also be utilized in the studio.

If you do use alkyd paints with painting mediums, especially dryers, be sure that those mediums are compatible with alkyds.

Paint With Faster Drying Pigments

All else being equal, certain colors or pigments will dry faster than others. Since many different color combinations can achieve the same results, you can utilize some of these faster drying colors on your palette. Also, toning the canvas with a quick-drying color can help speed up the drying time of the subsequent layers.

Colors that dry fast include:

- Raw and Burnt Sienna

- Burnt and Raw Umber

- Prussian Blue

- Cobalt colors such as Cobalt Blue, Cobalt Yellow and Genuine Aureolin

- Manganese colors such as Manganese violet, Manganese Blue and Manganese Black.

- Colors that contain lead including Lead White, Cremnitz White, Flake White

- Chrome Yellow and Red

- Naples Yellow

Colors that dry very slow include:

- Cadmium colors such as red, yellow, green, etc.

- Blacks such as lamp, carbon, charcoal and ivory.

- Vandyke brown.

- Vermilion.

- Alizarin Crimson

- Zinc White

Bear in mind that with the faster drying colors, some manufacturers will make them with a slower drying oil such as safflower to slow the drying time.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Be sure to avoid using very slow-drying colors listed above for your initial layers of paint. Adding a quick-drying color over a slow-drying color can result in cracking.

Paint On an Absorbent Surface

When it comes to canvas and painting surfaces, many beginning artists do not realize that there are other options besides the universal-primed canvas you see in stores like Michaels and Hobby Lobby which tend to result in slower drying time for oil paint. Here is a list of some options:

Lead-Primed Linen

On of my favorite surfaces to paint on is Lead-primed linen. Painting on a smooth canvas that has been double or triple primed with lead white is a beautiful experience.

The surface will slightly cling to the wet paint, which makes it great for wet on wet painting, but it will not stain and it's non-absorbant, so you can wipe wet paint completely off. Despite it being non-absorbant, oil paint dries much faster on lead-primed linen than it does on universal or regular titanium oil-primed canvas.

Bear in mind that lead is toxic, so be sure not to ingest it in any way. Also, its toxic nature makes it difficult to come by and it's expensive. There are a few manufacturers that make it but it may take some research. Some vendors will say their linen is lead-primed when it's really not, so inquire specifically before buying.

Lead white also has a tendency to yellow over time. So don't be surprised if you buy some lead-primed linen and see it's slightly yellow in appearance as compared with titanium-primed surfaces.

Alkyd-Primed Surfaces

Alkyd is more absorbent than titanium/oil-primed and lead primed surfaces. Paint will not spread as easily and it soaks in more, but it does dry faster.

Gesso-primed surfaces

There are two types of gesso, traditional gesso which is made with rabbit skin glue (poor bunnies), and acrylic gesso. Traditional gesso is meant for rigid surfaces due to its brittle nature, so only use it on something stiff like wood panels. Acrylic gesso is not a true gesso but just an acrylic primer. Glue chalk gesso-primed surfaces have an absorbent surface that will help oil paint dry faster.

Use Acrylic Paint for Initial Layers

This process may not speed up the drying time of your oil paint, but it can speed up the entire painting process. Many paintings are built up with a layering process which allows the artist to more easily establish color and value masses from which to work off of. Rather than using slow-drying oils for the block-in, you can use acrylics that dry in a matter of minutes. Once you are confident that the colors and values are correct, use oil paint for your final layers.

The great thing about this process is that there is less of a change of ghosting, those dull spots that happen when layered oil paints dry. This is especially true if you save the oil for your final layer. Not only will your initial strokes be thin, but they will contain no oil, so the fat over lean/thick over thin rule will be adhered to.

It's important to note that you must use a universal/acrylic-primed surface for this technique. You can always put oil-based paint over water-based paint, but never the reverse. So never use oil-primed canvas with this approach and never paint acrylic over oil.

Additional Factors That Influence Drying Time

As you can see, there are a number of factors that can influence the drying time of oil paints. So if one of the above approaches is not working, it could be due to another variable. For example: let's say you are painting on an absorbent surface but the paint is taking forever to dry. It may be that the paint is a pigment that normally takes longer to dry such as cadmium. And if that cadmium is made with safflower oil, it will take even longer.

I once used a brand of titanium white that was made strictly with safflower oil. I had a thick stroke of almost pure white paint in one spot on a painting that was supposed to go to a show. I was also storing the painting in our dark, unheated basement during the winter while it dried. Because of this combination of factors, thick paint, safflower oil, and a cold, dark environment, it literally took over a month before that one spot on the painting dried.

Other variables that can affect drying time are the brand of paint used. One brand of cobalt blue may dry faster than another brand, especially if the one brand has a lot of additives.

You also need to consider the age of the paint. If a particular tube of paint has been in a retail storeroom for years and it wasn't sealed airtight, it will probably dry faster since the oxidation process had begun prior to you receiving it; it may also be very stiff. The next time you order that same type, it may be a newer tube that will take longer to dry.

Given all the variables listed, it's impossible for anyone, even paint manufacturers, to offer 100% assurance on how long it takes oil paint to dry. The best thing to do is experiment with some of the options listed above until you determine what works best for your painting method, style, and environment.

I hope that helps. Please leave your questions, comments or experiences below. Thanks and keep painting!

Jason Tako is a nationally known fine artist who specializes in western, wildlife, plein air, and Historical Native American subject matter. He spent his learning years sketching the wetlands and wooded areas of rural Minnesota. He has been featured in Plein Air Magazine and Western Art Collector Magazine and he was the Featured Artist for the 2020 Southeastern Wildlife Expo. See his work at www.JasonTako.com and his demonstrations on his YouTube Channel.

So you have a nice drawing that you would now like to paint, and you want the painting to be bigger than the drawing. How do you turn your small drawing into a larger painting and enlarge the drawing onto the canvas?

There are several ways to transfer a smaller drawing onto a larger painting surface. The Grid Method breaks the drawing down into squares, and each square is copied onto the larger surface. You can also use the Measurement Method, an opaque projector, or enlarge the drawing digitally.

Below we look at each process in detail so you will have the best success with enlarging your drawing and turning it into a painting.

Enlarging Your Drawing with the Grid Method

This is the most time-honored approach, and probably the most painstaking. Yet it works well for those who don't have an opaque projector or the means to do digital enlargements.

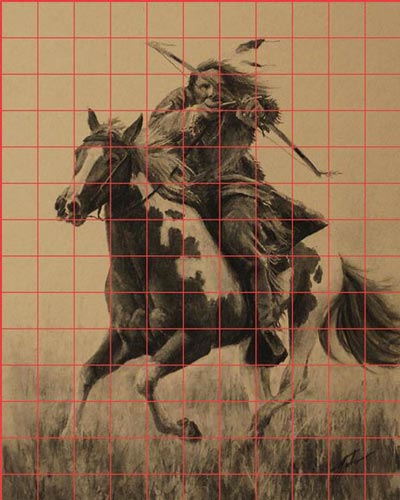

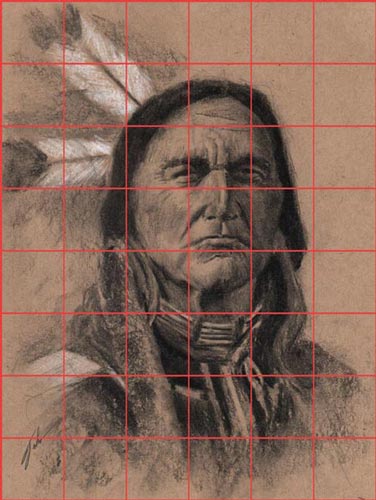

The basic principle is that you subdivide both the drawing and the painting into small squares. Then you can replicate the shapes in each square on your canvas. Once they are all replicated, you have a larger version of your drawing complete with correct proportions. It's a great method, especially for complex compositions where accuracy is a must, though it does have drawbacks you must be aware of.

How to Create a Grid

To do this right you must make sure that your larger painting surface will be the same proportion as your drawing. So in other words, if your drawing is 6 x 8 inches, your larger painting can be 9 x 12, 12 x 16 or 18 x 24 inches, since those proportions are the same.

In order to make sure your proportions are correct, you can buy a Proportional Scale at an art supply store for around $7 (see Blick Art Materials for current price), or you can just visit a free online proportional calculator such as this one at http://www.madametalbot.com/13/scale.htm. There are also apps that you can download onto your phone.

First, you will want to start by making 1-inch squares over your drawing. If you don't want to draw lines over your original drawing or sketch, you can create a replica by tracing over it with tracing paper and drawing the grid lines on the tracing paper. You can also print a photocopy and draw the grid lines on the copy.

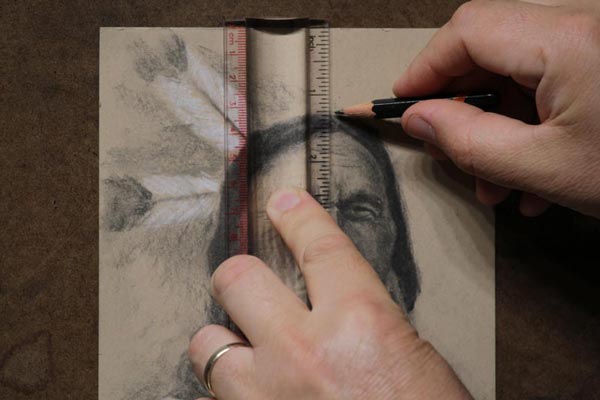

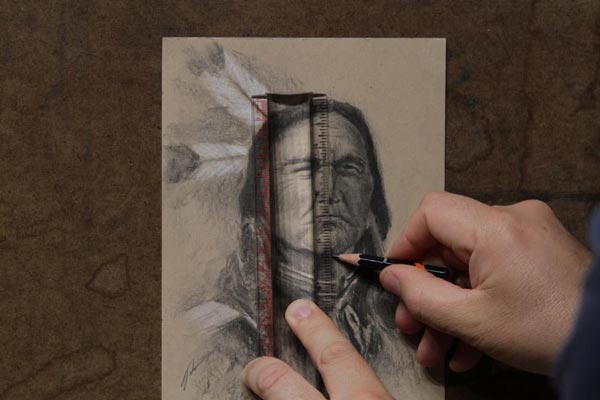

Whatever you do, just make sure your lines are straight. Use a ruler to make 1-inch marks on all four sides of your drawing, then use a ruler to connect these dots by making perfectly straight lines.

IMPORTANT NOTE: If your drawing has shading and tone and it not just an outline, you may want to create an outlined version of it with tracing paper since you may have a difficult time seeing gridlines on a fully shaded photocopy. Another option is to lighten the photocopy with photo-editing software like Adobe Photoshop.

Now you need to figure out what size to make the squares on your larger painting surface. There is a simple formula to figure this out: Divide the dimensions of the painting by the dimensions of the drawing.

For example, let's say your drawing is 6 x 8 inches, and you want to enlarge your drawing onto an 18 x 24-inch canvas (or a 13.75 x 11-inch drawing into a 20 x 16-inch painting as illustrated below). Divide the height of the painting by the height of the drawing, then divide the width of the drawing by the width of the painting. So 18 divided by 6 equals 3, and 24 divided by 8 also equals 3. In reality, as long the proportions are the same between the drawing and the painting, you only need to divide either the height or the width, not both.

So in the above-written example, the squares on your painting will need to be 3 inches while the squares on your drawing are 1 inch.

Applying the Grid Onto Your Canvas

The process of getting the grid onto your canvas is essentially the same as getting it onto your drawing. Still using an 18 x 24-inch canvas as an example, with a pencil, create dots 3 inches apart on all four sides of the canvas. Then using a yardstick, draw straight lines to connect the dots and create squares.

If your painting is larger than the yardstick, you may need to create dots 3 inches apart (or whatever spacing is required) somewhere in the middle of the painting. Line up your ruler or yardstick by using the dots on the side of the painting with the dots in the middle, draw your lines, then repeat on the other side of the canvas to complete the lines.

Once you have the grid on your canvas, you can start replicating the drawing. Below is another example, this time taking a nonstandard-sized drawing (13.75 x 11-inches) and converting it into a 20 x 16-inch painting. The grid for the painting ends up being 1.45-inch squares. Notice how I had to cut off the row of squares at the bottom due to the unusual layout of the drawing.

Other Helpful Tips for Using a Grid

Subdividing Squares for Details and Precision

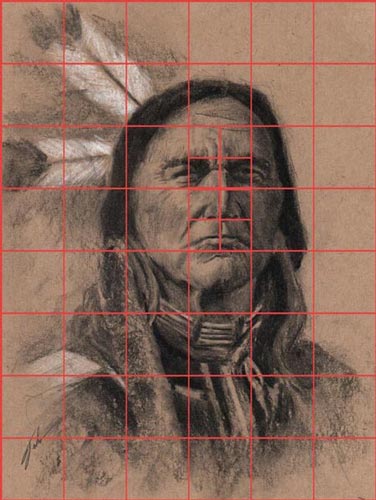

If your subject matter contains parts that are very detailed or require absolute precision, you can subdivide the squares in those areas to get more precise shapes. I do this when it comes to certain things like faces or hands. Using the 18 x 24-inch canvas as an example, in complex areas subdivide the squares on your drawing to be 1/2 inch, and the squares on the painting to be 1 and a 1/2 inch in size.

Numbering The Squares

If your composition is complex and/or you have a lot of squares to deal with, numbering the squares can help you keep track of which square you are actually working on. Nothing can be more frustrating than spending a couple of hours transferring your composition only to learn that you were off by one square and you need to erase everything and start over, leaving your canvas with messy, residual graphite.

Creating a Grid on Tracing Paper for Repeated Use

If you plan to use the grid method in the future, you can save yourself some time by creating a grid of 1-inch squares on a sheet of tracing paper or a sheet of acetate which you can then lay over the top of your drawing. Just make sure that the grid doesn't get moved once you have it lined up. Paper clips or mounting the grid and the drawing together on a clipboard can help.

The Pros and Cons Of Using the Grid Method

The pros of using a grid are that it's probably the most cost-effective method available. All you need is a rule or a yardstick and a pencil. It also gives you the confidence of replicating your drawing with correct proportions. You can make all your corrections, erasing, adjustments etc. on a smaller piece of paper, and accurately replicate that drawing.

The cons of using a grid are that once the drawing is transferred, you still have all those squares on your painting surface. You can erase those squares, but depending on your medium that could prove difficult. Plus you may end up accidentally erasing some of the actual drawing. This is why the grid method is best used for opaque mediums such as oil.

Transfer Your Drawing by Using the Measurement Method

This method is similar to using a grid yet without all the lines. Instead of drawing a bunch of squares, you measure the primary shapes on your drawing, increase their size proportionally, draw measurement dots on your canvas, and freehand draw the larger shapes on your canvas. Let's look at an example below.

Let's say you want to paint a human figure. We will once again use the example of taking a 6 x 8-inch drawing and transferring that to an 18 x 24-inch canvas in vertical format.

First, you will need to determine the starting point. Let's say the top of the head is 1.25 inches down from the top edge of the drawing. Use the above formula of dividing the size of the painting by the size of the drawing, 24 / 8 = 3. So all of your shapes will need to be increased three times. Moving to the canvas, the top of the head will be 3.75 inches down from the top edge of the canvas. Make a dot or small line on the canvas to mark this spot.

Repeat this same formula for determining the distance of the left side of the head from the left side of the canvas, then repeat for the right side, making small dots or lines to mark these spots. You should now have the correct placement of the head on the canvas.

Now you can work on measuring the distance from the top of the head to the bottom of the chin. Let's say this distance is 3.25 inches on your drawing. Once again multiply that by 3 which will tell you that the distance from the top of the head to the chin is 9.75 inches. Now you have the correct size of the head measured out.

You can do this for the distance between the eyes, the length of the body, and so on. You can even use it to figure out proper angles. Say you have a slanted leg in your drawing and you want to figure out the proper degree of the slant. Measure the distance of the top of the slant from the edge of the canvas then repeat with the bottom of the slant. Mark each spot and draw a line to connect the dots.

At some point you may want to pause your measurement process and start drawing some rough outlines so you don't forget what each dot or dash represents.

The Pros and Cons Of Using the Measurement Method

The Measurement Method is just as cost-effective as the grid method, all you need is a ruler and a pencil. It has one big advantage over the grid method in that you are not creating a bunch of excess lines that will need to be erased or painted over. This makes it more attractive for transparent mediums such as watercolor.

The disadvantage is that since you are only marking measurement points and not replicating shapes in small squares, your drawing skills will need to be on par for the task. The silver lining is that if you are confident in your drawing skills, you have more freedom of expression and feel less like a machine copying little squares.

I like using this method for simple composition that requires accuracy, like single a horse with a rider, or even portrait-type work. It can work great for landscapes also.

I will also use this method when creating my original drawing from a photograph. I don't use any math, I just compare the shapes with one another using a drawing compass to measure. I may also make the drawing the same size as the photograph and use the drawing compass to measure the subject matter in the photo and make measurement marks on my drawing. I get correct proportions without the scruples of tracing.

Enlarging Drawings with Opaque Projectors

Probably the quickest and cleanest enlargement and transfer method available to artists. An opaque projector will project an image of your drawing onto a larger surface allowing you to trace the illuminated image onto your canvas.

The Pros and Cons of Using an Opaque Projector

The great thing about it is you don't need to do any math, create grid lines that later need to be erased, or do numerous measurements. You just place your drawing on the projector, turn off the lights, project it onto your canvas and trace it. Once done you have an accurate enlargement of your drawing and nothing else. Some projectors like the Artograph Prism will also reduce drawings as well as enlarge.

Some things you should be aware of with projectors. First of all, this is one of the more expensive method for enlarging your drawings. There are some cheaper options out there but they are more limited in how much they will enlarge your work and the copy area is smaller.

Artograph has a small projector for around $90, but while it enlarges up to 14 times, its copy area is only 5 x 5 inches. Artograph's Prism projector, which runs around $260 (which I own) enlarges up to 20 times and has a slightly larger 7 x 7-inch projector area.

So for example, let's say you made your drawing 9 x 12 inches. In order to use it with the Prism projector, you'd need to make a reduced copy of the drawing so that the longest dimension was no more than 7 inches. You can also try to slide the drawing through the projection area and hope you get it all to line up correctly.

Another thing to be aware of is that if you are going to enlarge the drawing significantly, you will need a large room because most of the enlargement is done by how far back the projector is from the target surface. If you are working in a small room, you can only go so large.

Another challenge is getting the projector to be the same height as your canvas. You don't want to project at an angle since that will distort your image. The projector should be a near-perfect parallel angle with the canvas. Artograph did make an adjustable stand but it can be a challenge to find and they run anywhere from $45 to over $100. So when I use mine I use a stool and stack books.

My personal experience is that when going real large, the lines can get a bit faded. So make sure the lines on your drawing are very dark and your room can be made dark enough.

How I Use My Opaque Projector

I rarely use my projector, even for large paintings. I'm not at all trying to dissuade you from getting one since they can be handy. I just find setting up all the conditions for it to work well to be a pain.

I have small children and pets, and if either the projector or my easel gets bumped during the tracing process it can be almost impossible to get everything lined back up perfectly. I'm also a bit suspicious about shrinking a detailed drawing down to 7 inches max, then blowing it up to several feet. There is probably no problem with this, that's just my own quirk.

If you want to invest in a projector, just be sure that you will make good use of it and you are aware of the things I mentioned above.

Another note about tracing photos. Some artists, even well-known artists will use projectors to trace photos. I don't do that. My personal belief is that drawing is part of the artistic process. That said, I have no issue with using technology to enlarge and trace what I have already drawn. This is my personal motto. Each artist must decide for themselves.

Enlarging Your Drawing with Digital Software

This is my primary way of enlarging my drawings for painting. I also have a background in graphic design, so it works well for me. Basically, I scan my drawing into Adobe Photoshop at around 200-300 PPI or DPI (pixels per inch or dots per inch), enlarge the image to my preferred size, then print it out.

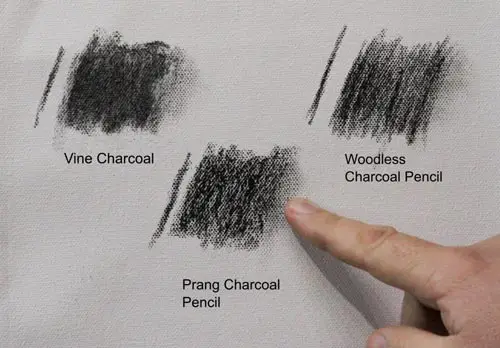

Once printed, I will apply either charcoal or graphite on the reverse side (just over the lines), then lay the charcoal side down on my canvas and trace over the image to apply the charcoal. You can also use carbon paper instead of drawing charcoal on the backside of the enlargement. Bear in mind that lines made with carbon paper can be difficult to erase.

Another variation for oil painters is to take a large piece of tracing paper and trace the enlarged drawing, apply oil paint on the reverse side, then lay it down on the canvas and retrace the image to apply the oil paint to the surface.

The Pros and Cons of Doing Digital Enlargements

What I like about digital enlargements is you don't have the uncertainty that can come with grids and projectors. Even with grids you may not draw those little shapes correctly, and projectors require you to shrink your drawing way down, possibly losing important details in the process. This doesn't happen with digital enlargements. You get an exact replica of your sketch and can enlarge it to an exact size.

Digital enlargements are fairly quick. You just scan in your drawing, make it bigger, and then print it out. It's also nice to know you can make as many copies as needed provided the file is saved. You can also darken the lines of your drawing and crop the composition to experiment with different layouts and proportions.

There are some drawbacks to using digital enlargements. The first being price. I use Adobe Photoshop, which is probably the top photo-editing software available and one of the most expensive.

Adobe has made Photoshop much more accessible with subscriptions for around $10 a month, and the software can be updated whenever there is an upgrade. This is much nicer than the old days when you had to buy a disc of the program for around $500 only to have it go out of date within a year or two.

Scanning Your Drawings

Another consideration is you will need a scanner to digitally scan your drawing. Flatbed scanners are going to work the best for scanning at home. At the time of this writing, you can pick up an 8.5 x 11-inch flatbed scanner for around $35. If you can afford it, I would go larger than 8.5 x 11 to save yourself the hassle of having to scan your drawing in sections and assemble with photo-editing software.

Office supply stores like Staples offer scanning services. If you don't mind making the trip and paying the fee for each scan, this is another option. At the time of this writing, many Staples stores have self-service scanning that allows you to scan up to 11 x 17-inch documents for under $1 per page. Bear in mind that the quality of the scan may not be as good as scanning high-res into Photoshop, but it may get you by.

Printing Your Enlarged Drawings

For printing my enlarged drawings, I usually use my cheap desktop printer that prints a maximum of 8.5 x 11-inch sheets. Because of this small size, I print my drawing out in sections, place these sections over a light table, cut off any excess, and then tape them together. Bear in mind some generic printer drivers may not allow you to print in sections; I do my printing directly from Adobe Photoshop so I can print in sections.

If I'm doing a really large painting, I will use Staples Blueprint printing service. You can get a digital file up to 36 x 48 inches printed for under $10 (locations may vary in price). The printing paper they use is pretty thin, but it suffices for applying charcoal on the back and tracing the enlargement onto canvas. Since this service is meant for blueprints, it only works for outline work. Your drawing shouldn't have any shading or color.

The other great thing about Staples Blueprint service is you can upload your file from home, submit the order, then either have it shipped to your studio or go pick it up when it's ready. This is my favorite way to enlarge my drawings for large paintings.

Additional Tips for Turning Your Drawing Into a Painting

When using the grid, measurement, or projection methods be sure to draw your initial lines lightly. This is always a good idea regardless, but since you may need to make later adjustments, it can be handy to not have to fight dark lines that are difficult to erase.

For making corrections on your painting surface, it's always a good idea to have an eraser designated for that sole purpose, especially if you are an oil painter. You don't want to risk getting oil residue from the primer into a nice pencil drawing.

Depending on what painting medium you are using, you can seal the drawing on the painting surface with a fixative spray. This will help prevent the drawing from getting smeared during the painting process. This will work for oil but may be a problem for water-based media, especially watercolor. I personally have never done this as I use my lines only as a guide, but many other artists use this method.

Another way to preserve your drawing on the canvas is to go over your lines with ink or paint and allow it to dry. Oil painters working on universal/acrylic-primed canvas can also seal their lines with ink acrylic paint. Just be sure never to use acrylic or any water-based medium over oil. Oil over water works; water over oil is a disaster.

Since I'm an oil painter, I usually use charcoal to transfer my drawing onto canvas, or carbon transfer paper for smaller drawings. I go into more detail about other possible mediums to use in my article, What to Use for Sketching on Canvas.

I also strongly recommend you do some small color studies before you attempt to turn your drawing into a file painting. Drawing is all about line and value; color adds a whole other dimension. You will have more success if you have a plan for your colors before you start on the final.

Do as many small canvases as necessary until you are confident about what your final painting should look like color-wise. Make sure you have sufficient reference material to work from, whether that is photo reference, additional sketches (color and black and white), or preferably both. If you begin to feel burnt out, work on another project for a while.

I hope that helps. Please leave any questions or comments below and keep sketching!

Jason Tako is a nationally known fine artist who specializes in western, wildlife, plein air, and Historical Native American subject matter. He spent his learning years sketching the wetlands and wooded areas of rural Minnesota. He has been featured in Plein Air Magazine and Western Art Collector Magazine and he was the Featured Artist for the 2020 Southeastern Wildlife Expo. See his work at www.JasonTako.com and his demonstrations on his YouTube Channel.

Using solvents to thin oil paint or clean brushes can present health problems for certain artists. But one does not need to abandon oil painting or resort to water-based oil paints due to intolerance of solvents. In this article, we will explore oil painting without solvents and what artists need to know.

Solvent-free oil painting can be done by thinning the paint with non-toxic mediums such as oils, natural alkyds, and even citrus-based thinners. Oil paint made from linseed or safflower oil does not produce harmful vapors and pigment toxicity is the same in both oil paint and water-based paint.

Below we will discuss some of these options in detail and what you need to know about each. I will also have links on my Resource Page showing where some of these items are available.

IMPORTANT NOTE: I'm using general descriptions for many painting mediums. When I say something such as linseed oil is non-toxic, it's not a guarantee since it's impossible to describe every manufacturer's production and refinement methods, and product misuse can make something non-toxic become toxic. Always check the brand label to confirm any possible toxicity or limitation of the medium.

Also, when trying a new product, I recommend purchasing a small amount and testing it first. People react differently to different things, and while something may be certified non-toxic, it doesn't mean you won't have a negative reaction to it.

One more note about oil paint toxicity. Many people mistakenly believe it's the oil paint itself that's toxic, and switching to acrylics or watercolor will remove all toxins, but this is false. As stated above, oil paint is just pigment in an oil binder, just as watercolor is just pigment in gum arabic. It's not the oil binder that's toxic, its pigments like cadmium or cobalt, and these are toxic whether the binder is oil or gum arabic.

So Cadmium Red watercolor is just as toxic as Cadmium Red oil paint. But bear in mind many pigments are non-toxic, and even the toxic pigments will not be toxic to you unless your skin is exposed to them or you sand a dry painting and breathe in the particles. Also, pigments do not turn into a breathable vapor unless your spray your paint onto the canvas.

Generally Two Ways to Thin Oil Paint: Solvents and Oil

Traditionally there have been two ways for an artist to thin oil paints: oil mediums, and solvents. Oil mediums include vegetable-based oils made from linseed, poppy, safflower or walnut. Solvents include turpentine and mineral spirits AKA white spirits.

The Different Oils Used for Oil Painting

Vegetable-based artist-grade oils are generally non-toxic. They're derived from the plant they are named after. So unless you have any allergies, using one of these oils is a good substitute for solvents. Oils do not produce fumes. In fact, they will absorb oxygen during the drying process.

Some artists may wonder which oil is best to use for oil painting. Let's look at each one.

Linseed Oil

Linseed oil is the primary oil used in most oil paint. It's permanent and very stable, providing a solid foundation. It generally dries within 5 days, depending on the paint thickness, pigment, air temperature, and type of surface it's applied to. The one drawback is it can yellow over time. This is more noticeable in lighter and cooler colors. As a result, some manufacturers will use a different type of oil such as walnut, poppy, or safflower for these colors.

Walnut Oil

Walnut oil is a pale yellow-brown color. It dries a little slower than linseed and is very resistant to yellowing and cracking. Colors in walnut oil can have a more brilliant appearance. It was used by some renaissance masters and is a great choice for artists who want to keep their studio solvent-free.

Safflower Oil

Safflower oil is paler in color than linseed oil and has less of a tendency to yellow over time. Its drying time is slower than linseed oil. Unlike linseed oil, which dries by forming a top skin, safflower tends to dry evenly throughout the entire film. This causes it to have a more sticky feel during the drying process which may not be preferred by some artists.

Some express concern over safflower's long-term stability, but analysis has shown it's held up well over the centuries and is used by many top paint manufacturers.

Poppy Oil

The slowest drying time of the bunch, poppy oil is great for artists who like to work wet on wet. It can give your paint a nice buttery feel. However, it should be used in small amounts as there are questions about its long-term durability, and if you plan to layer your paints avoid using it in your initial layers.

Oil Painting with Stand Oil, Alkyds and Others

Over the centuries artists and chemists have experimented with heating oil and exposing it to the elements to alter is viscosity and drying time. This altering usually does not result in any toxicity, but as stated above always consult the manufacturer's label.

Stand Oil

Stand oil is linseed oil that has been thickened by heating. The result is a thicker medium that has less of a tendency to yellow with a slower drying time than regular linseed oil. When applied, it spreads out reducing brushstroke texture and dries with a smooth finish, similar to enamel. It's great for glazing and usually low or non-toxic and like most oils, it will not emit any harmful fumes.

Sun Thickened Oil

This is an oil that has been exposed to sunlight to change its viscosity to a thick, syrup-like consistency similar to stand oil but with faster drying time. Like stand oil, it has less of a tendency to yellow. Unlike other mediums, you can apply it to your pigment with a much higher pigment to oil ratio without any breaking. You can easily make this stuff yourself. Check out Michael Harding Oil Colors to learn more.

Alkyds

Most alkyd oil paints are made with an alkyd resin binder. They dry quickly and create a very permanent surface.

Some alkyds can be toxic, others non-toxic, depending on the manufacturing process and ingredients. Gamblin's Galkyd is less toxic than others but it does release Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC's) and petroleum distillate that may cause some people to have issues. I personally use it (with adequate ventilation), but someone who is concerned about harmful vapors may want to avoid it.

M. Graham & Co. makes walnut alkyd that is certified non-toxic. The Walnut alkyd dries very fast and leaves a glossy surface. It also doesn't have much of a smell which is great for people with sensitive noses. I love using this stuff if I have to touch up an area that needs to dry very quickly and glossy.

Natural Mediums and Thinners for Oil Painting

In recent years there has been a push to create alternatives for non-toxic oil painting. Here is what you need to know about some of these options.

Citrus-Based Turpentine

There are now several citrus-based turpentines on the market such as Zest-It and Seville Citrus Turpentine. They are technically turpentine, but these are derived from orange peels rather than pine trees or forest waste (which are the sources of traditional turpentine). They are also technically non-toxic provided they are used correctly. Always read the label.

I have never used Zest-It, which is made in Great Britain, but reviews say it has a mild citrus scent and doesn't seem to cause the same issues most people have with traditional solvents. They also say it does a nice job of thinning oil paint. There are reports of skin sensations such as tingling, but this may have been due to people leaving it on their hands long-term causing it to eliminate the natural oils on the skin.

IMPORTANT NOTE: No painting medium should be left on your skin for long periods of time. Even completely natural solutions can cause skin irritation if there is long-term exposure. Wipe your brush handles often as medium running from the bristles down the handle is one of the biggest sources of skin exposure. Another solution is to paint while wearing latex gloves.

Oil of Spike Lavender

Oil of Spike Lavender (Spike Lavender is a type of Lavender flower) has been used since the 16th century. It thins paint well but has a very strong scent and some people report being unable to use it due to the strong smell which can even stay in your oil painting. It is considered non-toxic but studies concerning long-term inhalation are lacking. I would test a small bottle first and use it with sufficient ventilation.

Thinning Oil Paint with Technique

Solvents and oils are not the only way to achieve the thinning of oil paint. You can also do this by laying down thin layers of paint straight from the tube. This may require a sturdy bristle brush and some good old fashioned elbow grease. It's also easier to do with a smooth canvas that has very little texture. The lack of texture means you don't have to work as hard to fill in all the little holes with paint.

You can also scrap excess paint off with a palette knife and then thin it more with a bristle brush.

Be Aware of the Fat Over Lean Principle

The fat over lean principle is very important to remember if you are using any type of oil or petroleum-based medium and paint. The basic concept is that you always want to make certain your top layers of paint have a higher oil content than your bottom layers.

So if you are thinning your paint with oil, the initial layers of pigment should have very little, if any additional oil applied; it should be applied with the consistency straight out of the tube. As you continue to add layers of paint, make sure they contain at least the same amount, but preferably more oil than the previous layer. Be careful not to add too much oil as this will break the pigment and not cover the preceding layer.

Ghosting-Dull Spots in Your Oil Painting

If you don't follow the fat over lean application method, you risk ghosting in your oil painting. Ghosting is when dull spots of faded color appear after the oil painting has dried. This is because the layers underneath, which incorrectly contain more oil, sucked the little bit of oil out from the top layers down to the lower layers. This can be fixed with a technique called oiling-out, which is basically brushing more oil onto the surface of the dried painting.

The other problem that can occur is cracking. Since the top layer doens't have as much oil, it becomes more brittle. When the lower layers expand or contract due to their higher oil content, the brittle top layer is not able to move along and cracks.

It's also a good idea to paint thick layers over thin layers. Thick layers by default should contain more oil than thin layers. You can glaze thin layers over thick layers, but the thin layer must contain a higher level of oil. Gamblin Oil Colors has a great tutorial on their website about oil paint structure.

Basically, if you use a layered approach to painting, keep your initial layers thin by using a medium that is not oil or petroleum-based (such as a citrus-based solvent), or just apply the paint thinly right out of the tube. Then increase the amount of oil as you proceed. Use the oiling out technique if ghosting appears.

Ventilation for Oil Painting

In theory, if you are not using any solvents or toxic chemicals, you shouldn't need to concern yourself with ventilation. However, it is always a good idea to have some kind of ventilation in your studio, and it is a must if you are using solvents that may contain even slightly harmful fumes. It is recommended that your studio air be changed 10 times per hour.